Dignum and Comerford were convict shepherds belonging to Charles Hotson Ebden who absconded from service to become notorious murderers and bushrangers on the Sydney Road in mid-1837.

In the early part of 1837, Charles Hotson Ebden decided to establish a station closer to Melbourne giving him access to ships and the quickly growing markets at Melbourne.

He set out from Yass with a team of convict shepherds and 10,000 sheep and travelled down the Sydney road.

Ebden split the mob placing Charles Bonney in charge of one, while he took the other.

Travelling behind them was George Hamilton’s overlanding party bringing sheep, cattle, drays and men intending to set up a station at Gisborne for Henry Howey.

The shepherds of all three overlanding parties were fearful of travelling into the wilderness because at that time Port Phillip was mostly unsettled and considered beyond the limits of civilization.

George Hamilton later wrote of the expedition giving details of the troubles caused by three of his men absconding when they crossed the Murray River.

One of the men, a middle-aged fellow complained he was too old to place his life in such peril and was last heard of walking north back towards the Murrumbidgee.

The other two followed Hamilton’s overlanding party being secretly fed at night by their comrades.

Charles Bonney later wrote that he was visited by George Hamilton who warned him there were two bushrangers hovering about the party who planned to rob either party.

When Ebden and Bonney reached Kilmore Bonney stopped with 1,000 sheep to set up a station while Ebden journeyed on towards Mount Macedon.

George Hamilton took up Gisborne and almost immediately his plans were in jeopardy when some of his men absconded leaving him shorthanded.

When Ebden stopped at Carlshrue, on the Campaspe River on 26 May 1837 three of his men absconded taking with them a horse, guns and provisions.

These were Dignum, Comerford and James O’Brien, known as ‘the shoemaker’.

Dignum was an alias, his real name was Hugh Jelling or Jellings and he was born in 1801. He was a weaver by trade and his crime was Highway robbery. Hugh was illiterate, a protestant, a widower with 1 female child and described as 5’4½” tall, fair, ruddy complexion, pock-pitted skin (suggesting he’d survived smallpox as a child) light brown hair, grey eyes, small scar inside left arm near joint. He was given a life sentence and arrived in NSW on the convict ship, Bussorah Merchant, on 14th December 1831.

Upon arriving in the colony he was set to work in leg irons on the roads but managed to escape and changed his name to John Dignum. He then offered himself to different persons, passing himself off as a free man. Dignum pretended on occasion to be dim-witted and was thirty-six years of age in 1837 at the time of Ebden’s journey to the Macedon ranges.

Charles Bonney later wrote that ‘Dignum was an old hand, and, according to his own account, had been guilty of all sorts of crimes, and had served sentences in almost all the penal establishments.’

George Comerford used the alias, William Cooper but newspaper and court reports refer to him as, Comerford.

Upon arrival in Sydney, he was assigned to work for Mr Ambrose Wilson of Penrith, but absconded from his service after six months.

Absconding from service was such a common problem in the early colony that newspapers ran lists of names and descriptions of runaway convicts.

Being an assigned convict meant you were required to perform your tasks and in return, you were housed, fed and clothed. But in short, you were a slave at your master’s beck and call 24/7.

George Comerford offered his services to Ebden somewhere near the Murray River.

Dignum and Comerford do not appear to have known each other before entering into Ebden’s service.

Comerford was described as mild-looking, slim made, tall young man with an intelligent cast of countenance and about twenty-two years of age. He was also described as “rather effeminate” and all agree he appeared a quiet youth, pleasing and placid, exhibiting nothing of the murderer.

The Sydney Monitor, Fri 1 Jun 1838 wrote that George Comerford was formerly a soldier, and was transported to this colony by sentence of a Court Martial for striking his sergeant. He was born 1815, County Tipperary, Height; 5 ft. 7 ½ which was considered tall in the early 1800s. Complexion: Sallow, Hair: Dark Brown, Eyes; Dark Hazel

Comerford’s arrival on the convict transport ship ‘Hive’ was a memorable experience as the ship was wrecked before it reached Sydney.

The vessel ran aground on a sandy beach during the night of Thursday 10th of December 1835.

The only loss of life occurred when the boatswain tragically drowned in the surf whilst trying to save a young crew member in difficulties. The young man himself washed ashore safely.

Painting of a shipwreck near the shore by Nicolaas Riegen (Dutch, 1827–1889)

Once word of the wreck reached Sydney, rescue ships were sent to pick up the remaining passengers, crew and convicts as well as the ship’s cargo. The Hive soon became a total wreck. (Jervis Bay Maritime Museum)

Dignum and Comerford were both in Ebden’s employ when they crossed the Murray on the 1st March 1837.

At that time it was commonplace to tell stories of the savage nature of the blacks to frighten travellers heading south along the Sydney road. (George Hamilton, Experiences of a Colonist)

Because of this Comerford had a great fear of the blacks and begged Charles Bonney to be allowed a brace of pistols to defend himself if it became necessary. Bonney obliged and later wrote that the pistols were returned without issue.

It was late May and the weather was very cold. The absconded men were hungry and turned to bush-ranging to survive.

Charles Bonney was in need of supplies and set out for Melbourne but before he left he warned his men to be on the lookout for bushrangers during his absence. However, when Bonney returned he found some of his men had absconded and joined Dignum and Comerford. – The Sydney Morning Herald Sat 23 Jun 1906 Page 8

George Hamilton was also suffering the loss of men. His overlanding party consisted of 4,000 sheep, 800 head of cattle, 12 men including a number of convicts. He settled at Gisborne and by the 31st July, less than two months after arrival Hamilton had proved himself a capable leader as A. F. Mollison’s diary states that, ‘…when I rounded Mount Macedon and passed through the township of Gisborne on July 31, 1837, Howey’s huts were already erected on the creek. Howey’s run extended along the creek towards Lancefield Junction.’

Dignum and Comerford and their seven companions lived rough in the bush following roads that were marked only by wheel tracks. May is a cold month with temperatures at night dropping below freezing. Food would have been difficult to source and hungry, cold men with little hope soon become fractious.

The men set out for Portland Bay, their provisions carried on the grey mare stolen from Ebden while Hamilton’s men were armed with three muskets plus a tomahawk. There were nine men in all.

After two days walking one of the men, John Smith whom they named ‘the shoe-maker’ approached Dignum and told him there was to be murder. He had overheard the other six men plotting to kill them.

According to Comerford’s statement, ‘…at the end of the second day’s journey I went a short distance from the rest of the party for water; while I was thus employed, Dignum was tethering the mare to a tree near me; I saw one of Mr Howey’s men, I am not acquainted with his name, but we called him the shoemaker, come to Dignum, and tell him, that the other six intended to murder us three; the shoemaker told Dignum also in my hearing, that he did not think the native (meaning me) would stand by and see it done.’

Between eleven and twelve o’clock that night Dignum, Comerford and the shoe-maker lifted the blanket that formed a shelter for the other men who lay asleep.

Holding a musket in his left hand and the tomahawk in his right, Dignum commenced sinking the tomahawk into the head of the first man lying on his left hand, and hit four with all his strength, as fast as he could.

As he struck them they groaned but never spoke afterwards. On making a blow at the fifth man, John Smith, the tomahawk flew out of his hand. The man woke and rose up and Dignum fired at him and drove the ball through his head. John Smith died immediately.

The shoemaker then came up to Dominic Sampson, one of Mr Ebden’s assigned servants and placed the muzzle of the musket close to his head and blew his brains out.

Dominic Sampson was 35 years old, married with 2 male and 3 female children and his occupation was a “House Painter/Sign Painter”, he was from Dublin and his crime was Highway robbery with a sentence of life. He arrived in the colony on 12th December 1835. – Convict records.

While the shoemaker murdered Sampson, Comerford discharged his musket into the fire to cause his companions to believe he was taking an active part in the deeds.

But Dignum was aware of this and re-loaded his musket and turned to the shoemaker, “I did not see Comerford strike a man at all.”

Dignum then raised his musket at Comerford and fired but missed.

The shoe-maker, concerned at Dignum turning on his fellow said, “If you would kill Comerford then you will also kill me.”

‘At that moment one of the victims began to groan and Dignum said, “It’s best to put them out of pain,” and seized his musket by the barrel, and the shoemaker did the same and together they beat them all on the head till both muskets were broken at the butts.’

We will never know if the above account was a truthful recollection of events as we only have George Comerford’s word of it. At the time of giving his statement to the police, there was no one to contradict him.

Immediately after the murders, Dignum, Comerford and the shoe maker built up a fire and the bodies were thrown in.

Comerford stated, ‘we all three assisted to throw the bodies into the fire. Some of them that were far from the fire, we placed on the bloody blankets, and dragged them across and burnt body and blanket.’

He mentioned one body was pitched into the fire in an opossum rug. This is an important observation because we know possum skin rugs were preferred by stockmen to woollen blankets which could become soaking wet. However, it would be a heavy item to carry.

Comerford said they burnt all articles stained with blood. ‘We then placed large logs of wood on the bodies and kept the fire burning throughout the night.’

The Australian, Tue 18 Jul 1837 adds to the details, ‘…Digman covered the blood and brains with dirt, and with a stick broke the skulls…’

The site of the massacre was Mount Alexander, around 65 miles north-west of Melbourne. In March 1838, Mt Alexander was taken up by William Bowman who also took up Tarrawingee in northeast Victoria.

After burning the bodies of their comrades, Dignum, Comerford and the shoe maker took the grey mare and headed for Portland Bay on a route established earlier by the explorer Major Thomas Mitchell.

This track was little more than wheel tracks in the dirt and they stopped upon reaching a tree with the name “Stapylton” cut into it.

This would be ‘Grant William Chetwynd Stapylton, Second in command,’ of Major Mitchell’s expedition. On 31st May 1840 while surveying the south coast of Brisbane his camp was attacked by aborigines and he was killed.

Near this tree, an argument arose between Dignum and the shoemaker about the road to Portland Bay and threats were made upon each other.

During the night, Comerford stated that ‘he awoke and saw Dignum take the tomahawk and strike the shoe-maker three or four times on the head, which killed him.’

They hid the body in long grass on the edge of a water hole then changed their minds and determined on going to Port Phillip.

A few days later the mare they had stolen from Mr Ebden knocked up and Dignum shot her with the musket and kept some of the meat to sustain them on the journey.

The site where they killed the horse was later mentioned by Joseph Hawdon in his 1839 diary written during his journey to Adelaide with Lieutenant Mundy.

He wrote; On Thursday 18th July 1839,

“After having travelled twenty-three miles, we halted for the night near a small hole of water; here we observed the bones of a horse; from its position, we concluded it must have been a blood mare belonging to Mr Ebden, and killed by the notorious Dignum and his followers for provisions.”

It is worth mentioning here that two days previous, on the 16th July, Hawdon and Alfred Mundy had stayed at a sheep station belonging to Henry Boucher Bowerman at Mt Mitchell (42 kms north-west of Ballarat).

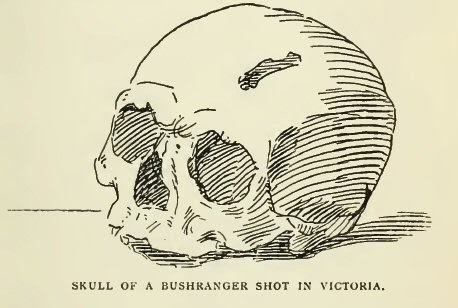

Hawdon wrote, ‘Mr. Allen (Bowerman’s foreman) showed us a human skull that had been found near here, with two fractures behind, apparently done with a tomahawk.’

They believed it to be a white man’s skull and Mr Allen said he intended taking the skull to Melbourne.

Comerford stated that about a week after the murder of the shoe-maker they reached Port Phillip and he and Dignum entered the service of Mr Egan – in other accounts, the name is spelt, Eagan and Aikin.

My research has been unable to locate with certainty the Mr Egan referred to. There was a Mr Stephan Egan of Vine Farm, Pentridge along the Sydney Road. But most likely it was also John Aitken of Mount Aitken. His stone home was at Diggers Rest near present-day Sunbury. He was one of the first white settlers in the district and the first to bring sheep to Port Phillip.

Dignum and Comerford were in Mr Egan/Aitken’s employ nearly a fortnight when Ebden discovered their whereabouts, placed them in handcuffs and locked them in a hut for the night. The next morning, after breakfast, Ebden and Egan were outside the hut talking and according to, The Australian, Tue 18 Jul 1837, Comerford said,

‘…the key of another pair of handcuffs lying nearby, Digman tried it … and as it fitted…we made our escape.’

At this point in time, the comrades of Dignum and Comerford were considered still at large.

Dignum grabbed up a double-barreled gun and held it to Ebden and Egan/Aitken while Comerford collected provisions.

They loaded the gear onto Mr Ebden’s horse and left with Dignum calling that no one should follow them else, ‘I will blow your brains out.”

Dignum and Comerford continued their escape but by taking a shorter route Ebden cut them off and demanded back his horse.

They again escaped and in Comerford’s statement, he said a short while later they realised they had left behind their blankets and it being winter, they snuck back to retrieve them.

During the retrieval of the blankets, George Hamilton got close enough to fire off a shot wounding Dignum in the hand.

They escaped on foot and headed for the sheep stations of Mr Bonney and Mr Burton.

Charles Bonney wrote an account of the robbery that then occurred which was reprinted in The Sydney Morning Herald, Sat 23 Jun 1906 states,

‘after being out all day on the run, I learned that two of the absconders, Dignum and Commerford, had visited the camp during my absence, and taken away with them as much provisions as they could carry; amongst other things, a favourite little gun, which had been made specially for my father when, from the growing Infirmities of age, he was unable to carry his double barreled fowling piece. Whilst the bush-rangers were robbing the camp the hut keepers asked them what had become of the other seven men who went away with them, to which they replied, in an evasive manner that they did not know.’

During the raid, one of Bonney’s shepherds, assigned servant, Frederick Hallem, said to Dignum, “John, I am sorry I did not go with you when you were here before, but I’ll go now if you will let me.”

Dignum agreed and the three packed the supplies onto a stolen horse and left for the Murray River.

- The Mr Burton mentioned here is likely, Judge William Burton who Charles Bonney worked for as a clerk for about nineteen months when he first arrived in Australia. Bonney resigned from his service to join Charles Hotson Ebden. It is possible Burton financed Bonney to set up the station.

Judge William Burton was the presiding judge of the second trial which found the stockmen guilty of the Myall Creek massacre on 10 June 1838 – an unpopular verdict with colonists.

Dignum and Comerford stole a horse, loaded it with the supplies and set off with Frederick Hallem towards the Murray River.

There was a sighting of the escapees travelling north on the Sydney road made by Thomas Walker in ‘One Month in the Bush’ in the vicinity of the Ovens River.

Charles Bonney wrote, ‘After the robbery, they proceeded along the overland track towards the Murray, and the next thing heard of them was that, on arriving at the Murray, Commerford gave himself up to the police then stationed there, and confessed that he and Dignum had murdered their seven companions.’

Bonney’s recollection on this is doubtful as official reports give a different version of events.

After eight days journey, Dignum and Comerford reached the Murray and according to Comerford, they concealed their firearms on the NSW side of the river then crossed back and approached Mr Ebden’s Bonegilla cattle station where William Wyse was in charge.

Comerford said they presented themselves to Wyse saying they had bolted from Port Philip, after having been apprehended by Mr Ebden.

The information of crossing then recrossing is missing from the statement made by Comerford but is found in The Australian, Tue 18 Jul 1837.

They gave William Wyse canisters of gunpowder along with a horse pistol and left Frederick Hallem in his care.

The next morning Digman and Comerford proceeded on to Mr Dutton’s station at Table Top run. The distance from the Murray River to Table Top is about 17kms, about a four 4 hour walk.

They then headed north to the station of the Catholic priest, Rev. J. J. Therry, at Billy Bong Creek, north of present-day Holbrook.

Here Comerford said they intended procuring rations and to furnish themselves with two horses with the view of returning to Portland Bay.

But as they arrived at Therry’s station, Dignum had a change of plan and told Comerford he would not return to the Murray but go on to Maneroo.

He then took from his pocket a certificate of freedom stolen from a fellow at Charles Bonney’s station and erased several parts of the description intending to use the document as his own.

Comerford said in his statement that Dignum then pointed a pocket pistol at him and said, “All I want is your life, you are the only man I have any occasion to dread.”

Comerford was the only man alive who could attest to their crimes. However, Dignum did not shoot and the two continued on to Mr Manton’s station at Tarcutta.

From here they travelled to Mr Frederick Jones’ station on the Murrumbidgee with the intention of parting company the day after.

But during the night Comerford told Mr Jones of the murders and about eight o’clock on Saturday evening, the 24th June 1837, Dignum was secured by Charles Tilson, assigned servant to Mr Jones.

Dignum denied any knowledge of the murders but confessed to the robberies.

For reasons unknown, Commerford insisted on divulging news of the murders and offered to take authorities to where some of the remains might be found.

Mr Frederick Jones forwarded a statement to the Magistrate at Yass, who immediately sent the mounted police to collect the prisoners.

Then not long afterwards a Chief Constable and two soldiers arrived from Port Phillip, with the man, Hallem, who had been left with William Wyse on the Murray.

The Attorney General examined Comerford and finding his story probable sent him to Port Philip so he might point out the spot where the murders were committed.

The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, Tue 15 Aug 1837, ‘The three men concerned in the horrid murder of Mr Ebden’s six servants were received into Sydney jail on Saturday last, forwarded by the Yass Bench to Sydney, for the purpose of being sent to Port Phillip for examination.’

Newspapers of the time reported the men all belonged to Ebden rather than correctly stating some had been assigned to George Hamilton and Charles Bonney.

Comerford travelled back to Port Phillip in the steamship James Watt but when they pulled into Twofold Bay, according to The Sydney Monitor, Mon 13 Nov 1837, ‘Dignum, one of the murderers of Mr Ebden’s men, who has become King’s evidence’, escaped.

‘It appears that the Captain who had been on shore had left his boat alongside; the constables who were in charge of the prisoner had retired below to get their dinner when the man contrived to slip his irons and escape into the boat and got ashore; he was soon missed and a search set on foot, but unsuccessfully for two days. It was only by procuring the assistance of a party of native blacks, that he was traced to a hut some miles from the coast, and apprehended as he was sitting down to dinner.’

It is confusing that the newspaper report wrote ‘Dignum’ but it is most likely a mistake as Charles Bonney in his Autobiographical notes wrote only Comerford was sent to Melbourne in order that he might show the place where the murders were committed.

ANOTHER MURDER

Upon the arrival of Comerford at Port Philip he was placed in charge of Sergeant Chim, and Private McDonald of the 80th Regiment, and Constables Partington and Matthew Thompkins,

The Australian, Tue 30 Jan 1838 reported,

“We started from Port Phillip on the 11th December and arrived at the place where the murders were committed. On the 21st we arrived at the spot described and found some human teeth, bones, buttons of clothes, nails of shoes, swivel of a musket, two pins of a musket, screw, a knife, one tin pot, and a lock of hair. We searched for the muskets in the adjacent water-hole, but could not trace them.’

‘On the 22nd we arrived where Mr Ebden’s mare was shot and found the remains of the body, excepting one leg. We brought in the head and a portion of the mare with us; on the 23d we returned towards Melbourne for rations. On Christmas Day we found a jacket which Comerford said he left there some time since, with some ammunition, and part of an opossum cloak; we proceeded on our journey until the 30th, and then arrived within about one hundred and ten miles of Port Phillip; on that morning at break of day, we started on our journey. At the end of about two miles, we missed our tea, when it was decided that Wm. Partington, of the Sydney Police, should go on with Private Macdonald of the 80th regiment, to look for it.’

Mean whilst, Matthew Thompkins, a constable of Port Phillip police and Sergeant Chin, 80th regiment, took charge of the prisoner Comerford, and were to wait at the first water-hole they met with, till their companions should come up with them, but they by some means missed the first water-hole and proceeded towards the next.

The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, Tue 29 May 1838 named the site as, ‘Deep Creek, near Port Phillip.’

Comerford was neither handcuffed nor ironed during this period which suggests police believed he posed no threat to their safety.

‘The sergeant placed his musket on the ground, while he went to get some wood for the fire, and Tompkins also incautiously did the same, while he busied himself about the fire, the prisoner seeing the favourable opportunity of escape, snatched up one of the muskets, and ordered Tompkins to stand off.’

Thompkins, who was standing near, said, “What are you going to do, John,” to which the reply was, “stand off, I don’t want to hurt you,’

This report is from The Sydney Herald, Thu 1 Feb 1838 and is confusing as it says Thompkins called out, “what are you going to do, John?”

This raises the question of was John Dignum present at the search for evidence? If so, then it was possible Dignum made the Twofold Bay escape.

Conflicting reports make unravelling events very difficult. This is even more pronounced later in the story as you will see.

Official reports say that Thompkins then made a rush towards Comerford, intending to seize him and Comerford levelled the gun and fired, the ball passed through Thompkins chest and right arm.

The sergeant ran up, but as Comerford had possessed himself of the other loaded musket, he ordered him to stand off and thus made his escape.

Partington and the other man shortly afterwards returned and found Thompkins mortally wounded.

On asking Thompkins what happened, he replied, “I’m shot by Comerford and the prisoner has escaped, and the sergeant is in pursuit of him.”

Partington and McDonald then went after a missing horse, which they found in the gully, then fired a shot to alert the sergeant they had returned. After this, they returned to their fallen comrade.

Mathew Thompkins entreated his colleagues not to leave him as he was afraid of being eaten alive by birds and native dogs. He lingered some hours and then expired and towards evening he was interred in his grave.

News of Thompkins murder and that the killer, Comerford was on the run caused great excitement in the area and there are accounts of events from numerous sources.

Charles Bonney wrote, Commerford made, ‘his way across to my station to attack me; but, calling at a hut on the way, the men at the hut knowing who he was and hoping to gain some reward for themselves, seized him and chained him to a dray.’

The Sydney Sportsman, Wed 19 Feb 1913, written by J.M.F. ‘Comerford, being short of provision’ ….’ entered a hut on a cattle station, and gave an order for breakfast, intimating that, he would shoot the first man that moved, other than to do his bidding….With his gun between his knees Comerford made a meal of damper, beef and tea, and then asked for tobacco, to have a smoke. One of the stockmen known as Kangaroo Jack suddenly reeled round, and dealt Comerford a terrific back-handed blow throwing him off balance, and held him in an iron grip. After a furious fight, he was seized and bound hand and foot and conveyed on a bullock-dray to Melbourne’. 1.

Further details are gleaned from the website of Port Phillip Pioneers,

‘John Aitken was visiting the station of Mr Howey (managed by George Hamilton) and became involved in the capture of an escaped convict named Comerford who had arrived there armed with a rifle and demanding a horse. Fortunately, another convict named Charles Cole who was working on Mr Howey’s station as a stockkeeper was able to help overpower Comerford and recapture him for which Cole received a conditional pardon.’

This may be true as many years later the Dubbo Dispatch and Wellington Independent on Friday 9th April 1915 printed a colourful tale of Comerford’s escape and recapture involving Kangaroo Jack. They said a reward of £60 was offered for his apprehension and a free pardon to any convict that might secure him. Subsequently, Kangaroo Jack gained his freedom and a monetary reward.

Was Kangaroo Jack an alias for Charles Cole?

Official reports stated Comerford was captured on the Monday morning, about ten o’clock, by three assigned servants of Mr George Hamilton, about forty miles from the settlement and that Comerford was lashed on a dray.

Yet there is a different version surrounding the murder of Thompkins printed in The Sydney Herald Mon 22 Jan 1838, that states four policemen were killed by Comerford.

‘Mr. Jennings, of Market-street, has a relation at Port Phillip, from whom he received a letter on Saturday, which contains some information respecting a horrible murder committed by Comerford……Subsequently, the bodies of Thompkins, Ford, and the two soldiers were found, lying together; they were all quite dead and had been shot. Comerford was afterwards seen about ninety miles from the spot with Thompkins clothes on. What has become of Partington or how Comerford possessed himself of the arms, for we presume that he is the murderer, we cannot understand, but the James Watt, on her return will probably bring full particulars of the whole affair.’

(The ‘James Watt’ being the steamship travelling between Sydney and Port Phillip.)

What actually transpired may never be known as Parlington, the constable, refused to say a single word on the subject, no doubt aware that the whole party had been guilty of gross negligence in suffering their prisoner to be out of irons, knowing his desperate character.

Years later, Charles Bonney pondered upon this and wrote, ‘It is still more difficult to account for Commerford’s conduct in giving himself up to the police in the first instance, and then committing the crime which led to his execution. He seems to have been a creature of impulse, and this was exemplified by his borrowing a brace of pistols from me on one occasion to protect himself, as he said, from the blacks, and having, within a day or two of his absconding, returned the pistols to me without my having asked for them.’ The Sydney Morning Herald, Sat 23 Jun 1906

Comerford’s act of killing a policeman rendered him unable to give evidence against John Dignum but his own trial was swiftly dealt with.

THE TRIAL

Supreme Criminal Court MONDAY, MAY 28, 1838

George Comerford was indicted for the wilful murder of Matthew Thompkms at Deep Creek, near Port Phillip, on the 30th December 1837, the prisoner pleaded guilty.

The Chief Justice said, ‘Are you aware that I have no discretion, but must proceed to pass sentence of death upon you’. Comerford replied, ‘Yes, your Honor, I offer up my life to God for the crimes I have committed.’

EXECUTION OF COMERFORD

Yesterday, pursuant to his sentence, George Comerford, who pleaded guilty to the charge of murdering Constable Thompkins, was executed.

Being a Roman Catholic he was attended by the Rev. Mr McEncroe, and although he was very firm appeared to pay particular attention to the exhortations of the reverend gentleman. He did not utter a word, except the responses in the religious duties he went through, from the time he arrived in the yard until the drop fell. After he had been suspended about an hour, his body was placed in a coffin filled with lime and buried within the walls of the gaol.

Dignum was never charged with the murders of his seven companions and the burning of their remains. Because there were no witnesses to testify against him he could only be charged with robbery of Ebden’s horse.

The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, Thu 9 Aug 1838 wrote,

‘John Dignum, alias Hugh Jelling, was indicted for stealing a horse, saddle, and bridle, the property of Charles Hotson Ebden, at Port Phillip, on the 4th day of June 1837. The jury returned a verdict of “Guilty” against the prisoner without leaving the Court. He was remanded.’

The Sydney Monitor, Mon 20 Aug 1838 reported, John Dignum was convicted of highway robbery and the judge asked his life be spared because he had not harmed Mr Ebden during the robbery. The judge suggested Dignum devote the remainder of his days to penitence and prayer and ordered that he be incarcerated at Norfolk Island and worked in irons till the end of his life.

On 18/8/1838 – Hugh Jellings was tried at the Sydney S.C Sentenced to Life for the robberies but this was commuted to 7 years.

1838: Hugh Jellings was sent to Norfolk Island.

12/10/1845: Hugh Jellings arrived Van Diemens Land per ‘Lady Franklin’.

On arrival in VDL Hugh Jellings was described as a Book Binder who can read and write*, RC, 40 years old, 5’5½” tall, ruddy complexion, brown hair, red bushy whiskers, grey eyes, stout made, small scar on right arm below elbow, scar on joint of left arm.

*Dignum had improved himself as his arrival record for 1831 described him as illiterate.

Footnote – Various accounts speak of Dignum finishing his life on the end of the hangman’s rope. The crime being the murder of a police sergeant killed during an attempted escape. I cannot find anything to verify this but future historians may be more successful!

FOOTNOTE: from court records,

Servants of Mr Ebden

John Smith – The reason why John Smith absconded is unknown for according to The Australian, Tue 18 Jul 1837, Smith was, ‘a free man’. It must be assumed Smith joined the overlanding party for wages but decided the work was not to his liking.

Dominic Sampson, ——Salby

Robert ….?

Assigned servants to Mr Howey managed by George Hamilton

Descriptions from; The Hobart Town Courier, Friday 16th June 1837 pg2

Uriah Sharland per Camden, fair ruddy complexion, one thigh has been broken and is bent outwards, height about five feet six or seven inches, a remarkable soft voice, age about twenty-six, an agricultural labourer, native of Wales.

(Further accounts of Uriah Sharland and the prisoners absconding can be found in George Hamilton’s book, Experiences of a Colonist)

William Stockam per Fairlie, a soldier about five feet eleven inches or six feet in height, dark sallow complexion, black hair, a slight impediment in speech, walks a little lame, age about twenty-five years, a native of England.

The shoemaker – James O’Brien per Hero, a native of Dublin, a soldier and shoemaker, about five feet six or seven inches in height, pale complexion, appears to be consumptive, speaks low, age about twenty-six years, dark hair.

THE REFERENCES;

(1) The Australian, Tue 18th July 1837, page 2 printed the statement of George Comerford which he made to Mr Jones on the Murrumbidgee after giving himself up.

(2) Charles Bonney, Autobiographical Notes found on TROVE. https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-360332043/view?partId=nla.obj-360333177#page/n2/mode/1up

(3) Private Letter recounting Comerford’s murder of Tompkins and the wearing of the dead man’s clothes. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/2549316?searchTerm=Comerford%2C%20Tomkins%2C%20murder%2C%20port%20phillip%201837%2C%201838%2C%20Digum%2C%20PP%2C%20court%2C%20murder%2C%20hang#

(4) Extra details of Comerford and the murder of Tomkinsn The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1871 – 1912) Sat 2 Dec 1893

(5) Description by Comerford of the murders of their comrades, Colonial Times (Hobart, Tas. : 1828 – 1857) Tue 29 Aug 1837