Lady Jane Franklin travelled from Melbourne to Sydney in April 1839 making detailed entries in her diary describing the scenery, plants, animals and the places they camped but most importantly, she wrote of her impressions of the indigenous people she met. Her diary gives insightful glimpses into life along the Sydney road during the early years of white colonisation. (1)

She was a strong-minded woman and well educated with much travel on the continent. Lady Franklin certainly had a love of adventure for she made her overland Melbourne to Sydney journey at age 48.

Jane, Lady Franklin, painted in 1838, by Thomas Bock, chalk on paper, held at The National Portrait Gallery.

Lady Franklin was the second wife of Sir John Franklin, Lieutenant Governor of Van Diemen’s Land 1837-1843.

Travelling with Lady Franklin was Dr Edmund Charles Hobson, a keen naturalist. (2)

Dr Hobson was born at Parramatta in 1814 and studied medicine in Hobart and abroad. His studies took him to France and Scotland. He also studied at the University College in London and his medical qualifications were obtained from the University of Erlangen in Bavaria. (3)

This unsigned oil painting of Dr. Hobson is held by the State Library of Victoria. He was a relative of Captain William Hobson after who Hobson’s Bay is named. (6)

Dr Edmund Charles Hobson married Margaret Adamson in Surrey, England on 27 September 1838 and the newly-weds set sail for Australia, arriving at Hobart, V.D.L. on 12 March 1839. On 1 April 1839, Dr Hoson left his wife with friends and boarded the ‘Tamar’ with Lady Franklin and her entourage heading for Port Phillip to commence their overland expedition from Melbourne to Sydney, New South Wales. (3)

Dr Hobson also kept a journal whose entries are printed alongside those of Lady Jane Franklin in the book, This Errant Lady, Jane Franklin’s overland journey to Port. Phillip and Sydney, 1839. (4)

When I first read Dr Hobson’s journal I pictured him as a much older man. He was, however, newly married and just 25 years old. The notes from his diary are usually read alongside Lady Franklin’s as together they give us a broader picture of their overland journey.

Included in Lady Franklin’s party was her cousin and constant companion, Miss Sophia Cracroft; Captain William Moriarty; the Hon. Henry Elliot; 2 servants (Mr and Mrs Snatchall ); the driver of the cart ( a convict named Sam Shelldrake); 2 mounted police, and a constable from Hobart to look after the horses.

They crossed the Goulburn River on 12th April 1839, the baggage going on Mr Clark’s punt and the horses and carts by fording.

Painting by HJ Johnstone, Twilight on the Goulburn River

At the Goulburn River, Lady Franklin wrote that a few weeks previous to her travels a servant of Mr Ebden’s was set upon by Blacks, stripped completely naked and robbed of rations and clothes. The police shortly afterwards found the tracks of the offending Blacks but all search for them was useless, ‘they twist round trees, hide & very slowly move, stand motionless like a stump. The district in which we were now entering between the Goulburn & Murray (rivers) is said to be most frequented by them.’

Dr Hobson noted in his diary on 12 April 1839 – the natives …..move at night which is a feature in their character marking at once their superior courage.

Too frequently we read historical accounts of indigenous people being dull-witted savages. Yet here we have descriptions of their almost magical ability to move unseen in the bush and nocturnal possession of ‘superior courage’.

On Saturday 13th April 1839, Lady Franklin’s party camped at Honeysuckle Creek which runs through Violet Town and she noted, ‘the light of common fires, in which some beautiful & gigantic moths one after the other sought their deaths’.

This observation is expected as Bogong moths which frequent the high plains during warmer months return to their breeding grounds in northern NSW during April & May. (7)

Bogong moths were an important source of fat and protein to indigenous people and they would travel to the high plains to feast upon them and return fat and sleek as noted by JFH Mitchell. (7)

Lady Franklin noted, ‘the Blacks ate great quantities of the Moths both in chrysalis & moth state, singed in the fire.’

The cooking method described here is that of rolling of months in hot ash to singe off wings and gently cook the bodies. (7)

An article in the Sydney Morning Herald dated October 12, 2013, said, ”The fried Bogong was crunchy, with an unusual flavour – very fatty with a faint almond-like after taste.

But because Lady Franklin described these moths as ‘gigantic’ it is more probably the rain moth that has a wingspan up to 17 centimetres and emerge from the ground leaving behind papery cocoons. These moths are called Trictena atripalpis, also known as bardee (bardy, bardi) grub and are found in the southern half of Australia.

Photo is from ABC South Australia, posted 7th April 2016

On Sunday 14th April Lady Franklin and her party arrived at the Broken River (Benalla) and she gives a description of the crossing place helping us to understand how it came by Broken River as its name. She wrote it was a series of dry water holes divided by bridges of earth wide enough to cross upon.

There was a shower of rain and Lady Franklin took shelter in a police hut that was under construction.

Just one year earlier the Broken River had been the scene of the Faithful massacre of 8 shepherds and due to public outcry, the government was placing mounted police on the river crossings.

There was a fire burning inside the police hut and Lady Franklin took advantage of it to dry an ‘opossum rug’.

Possum skin rugs or cloaks were the principal clothing of indigenous people and Europeans quickly adopted this article of clothing when in the bush recognising its superiority in warmth and ability to stay dry. Possum fur sheds water thus keeping the wearer dry. (5)

William Thomas, Assistant Protector of Aborigines in the Western Port District, saw many Boonwurrung and Woiwurrung people ‘dressed comfortably’ in possum skin rugs, giving them a ‘majestic appearance’. (8)

Newspaper reports also confirmed Thomas’s view. The Illustrated London News described the manufacture of ‘very warm and beautiful cloaks of opposum skin, which they wear with the hair side inwards, the other side ornamented with geometrical patterns drawn with wonderful accuracy’.

Official reports and personal correspondence describe the colonists using possum skins for a range of different purposes, most of them mimicking the traditional uses. Edward Curr, (9) a young squatter at Port Phillip in 1841, wrote of a typical overseer’s hut having an ‘opossum-rug’ spread over the bed. In January 1838 Matthew Tomkin, a mounted police constable, murdered near Mt Macedon (north-west of Melbourne). Tomkin’s friends ‘buried him, having wrapped him up in an opposum rug’. (10)

The demand by pastoralists and their servants for possum skins and especially possum skin rugs were widespread. So popular was the latter that a small number of white entrepreneurs established a lucrative trade in the skins. GA Robinson, Chief Protector of Aborigines in the Port Phillip District, observed how a number of pastoralists and merchants in Melbourne and the ‘settled districts’ had become wealthy from the considerable inter-cultural trade in artefacts such as possum skins and lyrebird tails.

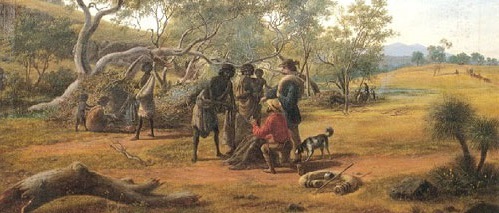

Title: `Barter 1854′ by Eugen Von Guerard

While Lady Franklin waited in the warmth of the hut one of the paddies or troopers told stories of the Blacks.

Lady Franklin and her party were fearful of attack especially since the graves of the shepherds killed at the Faithful massacre were nearby.

One of the men at the hut assured them they were safe saying Blacks would have seen them, ‘the whole way but they would not venture to attack as Lady Franklin and her party were too many….they will attack two or three but not five or six.’

This observation is in contradiction to WP Faithful’s party of shepherds which was 18 in number when attacked. This adds weight to the theory that the attack on the shepherds was not opportunistic but rather a planned event in retaliation for something the shepherds had done.

Afterwards, Lady Jane Franklin was taken to see the massacre site and must have heard many stories of the brutal attack. That night in her journal she wrote, ‘The intelligent Corporal at the Broken River said that many stories told of the blacks were false.’

Lady Franklin was told the Blacks campaign against Mr Faithful was, ‘lasting and at last counting of Mr Faithful’s sheep, 600 were missing—he is now at his 3rd station since his men were killed and is going to shift again on account of the blacks.’

She does not elaborate to which Faithful brother she was referring to. WP Faithful may still have had his men and animals in the area seeking a suitable place to squat meanwhile his brother George, had set himself upon the Oxley plains.

WP Faithful already had a fine station at Goulburn named ‘Springfield.’

Lady Franklin wrote ‘Mr Faithful’s neighbours do not suffer in the same way.’

Just why was it that Faithful’s neighbours, ‘do not suffer in the same way.’ What had the Faithful brothers and their men done to indigenous people to have the Faithful’s singled out for repeated attacks while their neighbours were not?

On Wednesday 17th April Lady Franklin arrived at the Ovens river and noted the ‘pretty scenery on the banks’ and that the ‘trees, particularly near the river, larger & greener, some destined to death by being ringbarked,’ and ‘the ground here is parklike.’

On Thursday 18th April they arrived at Joe Slack’s Barnawartha station located at Indigo Creek.

Lady Franklin wrote, ‘Joe Slack has lately quit’….’selling to a person of the name Hume one month ago.’ She said, ‘Joe Slack, the late proprietor, was once a prisoner, but being diligent and sober and industrious had got on and is said to have £3000.’

The diary gives a good description of the establishment, ‘The hut is of gaping boards, divided in 4 chambers without doors, covered with slabs of bark—an open shed for the stable.’

While the hut was unoccupied there was an indigenous man keeping an eye on the property.

‘We found a native in European clothes with a pipe in his mouth hanging about the hut—he is employed there.’

On Saturday 20th April they came to the Murray River and saw a field of maize edging the banks on the other side. This crop belonged to inn keeper, Robert Brown and was his first crop.

Lady Franklin noted, ‘the river here made a great bend then descends to a pebbly beach. The ford was up to the horses’ bellies and the opposite bank was very steep.’

They encamped within the fenced paddock of the mounted police station where 4 policemen lived in a 4 room hut which was neatly kept with a nearby hen house for half a dozen fowls.

An aboriginal couple was employed to bring wood and water and they spoke a little English.

There were two other dwellings at the crossing place at that time. Near the police hut was a smaller one belonging to Mr Lewis whose cattle station they passed 2 miles on the other side of the river, the other, ‘the spacious hut Mr Brown has erected for a store.’

Lady Franklin gives an account of the trust Robert Brown placed in the indigenous people he employed when she wrote, ‘A native black named Jem, dressed in jacket and trousers, with his gun by his side and a pipe in his mouth was squatting on the ground by the side of Mr Brown’s maize field.’

Jem was employed to frighten away the crows that came to feast on Brown’s maize or corn crop and it shows a great level of trust that Jem was unsupervised and in possession of a loaded gun.

This is intriguing because after the Faithful massacre CH Ebden wrote letters stating the blacks in this area were treacherous and needed to be brought under control.

It is also confusing when we consider Merriman was said to be one of the ring leaders of the massacre of Faithful’s shepherds yet it was Merriman who advised Robert Brown where to plant his crops and was employed to ferry passengers in his canoe when the river was in flood.

The story of Jem and his loaded gun reminds us of the words of the intelligent corporeal who said, ‘many stories of the blacks were false.’

Lady Franklin gives an insight into Jem writing he had, ‘the loss of two front teeth in his upper jaw (one of the distinguishing marks of his tribe) and by a pendant ornament to his shock-head consisting of two kangaroo teeth fastened by strings to the twisted hairs. I heard a good account of the useful and amiable properties of this man.’

GA Robinson also writes of the practice of tying kangaroo teeth in the hair at the temples saying it was a wide-spread practice. (11)

Lady Franklin wrote about the indigenous man named Joe who worked alongside his wife and daughter at the police hut. She wrote, ‘we were told that Joe used his gin, (wife) very kindly.’

Lady Franklin and her party continued north towards Sydney making note of the people and places. Reading her diary we find on the border of Kyamba Creek they met a large herd of cattle belonging to Mr Chisholm that were going to his station beyond the Murray and with them was a female trudging along with his party.

This is a fascinating observation that shows us that white women may very well have been travelling the Sydney road much earlier than historic records show. It was believed Lady Frankiln was the first white woman to make the journey but her record of the woman travelling with Chisholm’s party suggests otherwise.

I have often wondered how cattle and sheep had enough grass to eat along the roadside when you consider how many were using the road. It was usual for herds to consist of hundreds of cattle and 3,000 or more sheep. Any squatter close to the road would have their grass eaten, their water holes fouled and any disease (such as catarrh) spread to their animals.

Lady Franklin wrote of the animosity that occurred between the landholders along the road and the overlanding parties.

She wrote of Mrs Smith, a disagreeable-looking woman who told her that herds and flocks encamped along the road near their farm ate the feed till there was none left for her animals.

‘Hence no doubt one cause of Mrs Smith’s sulkiness,’ wrote Lady Franklin.

In April 1839 the drought was three years into its hold over the land and Lady Franklin wrote about a man who earned his living ploughing. He told her, ‘the ground till lately could not be ploughed,’ the crust too hard.

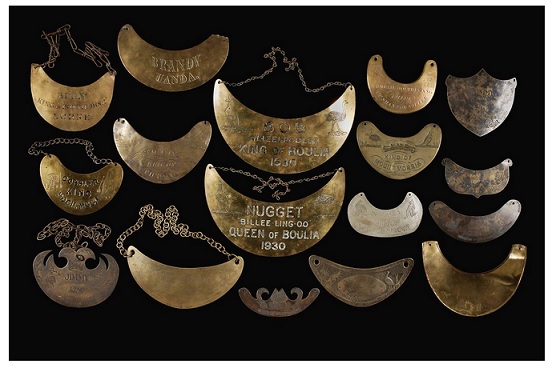

At Tarcutta creek on Thursday 25 April, Lady Franklin wrote, ‘we saw several fires of natives and went up to see them. One man, who wore a shirt and a crescent shaped flat piece of copper by a chain round his neck, which had been given him by Mr Manton and a neighbouring squatter who had also presented him with a suit of armor, made also of copper, and which they keep for him.’

The photo shows an array of breastplates or King plates from the National Museum’s collection

King plates or gorgets were given to Aboriginal men and women, who proved themselves useful to the white men. The plates were presented to perceived ‘chiefs’, courageous men or faithful servants. Some Aboriginal people wore their breastplates with pride while others saw them as yet another insult to their culture from the white invaders.

The name engraved on the plate Lady Franklin saw was ‘Dabtoe, chief of the Hoombiango’ – its present location is unknown.

Lady Franklin wrote, ‘Dabtoe and two others, all in cotton shirts came to throw Boomerangs.’ ‘It goes level some way and then rises above the trees, flutters like a bird in the air then skims or floats and returns, dropping at the man’s feet.’

Lady Franklin must have spoken to Dabtoe and his fellows about the massacre of Faithful’s shepherds because she wrote in her diary, ‘When speaking of the head chief at the Ovens who had speared white fellows.’ ‘You’d fight him, Dabtoe, would not you?’

‘I believe so’, he replied.

When Lady Jane Franklin arrived near Goulburn she dinned with Alice Gibson, William Pitt Faithful’s sister.

Lady Franklin wrote, ‘At dinner we were joined by Mr Faithful, Mrs Gibson’s brother, a bachelor, living 5 miles off, the same who had his men speared about a year ago at the Broken River.’

William Pitt Faithful was still a bachelor so perhaps it was the charms of his sisters esteemed guest that made him speak freely about the attack on his men at Benalla. The information he gave her was missing from reports at the time.

He said, ‘His men had been intimate with them (the natives) and given them much food— they had but 4 muskets among them—amused themselves with firing at target against gum tree—3 never hit—the natives laughed & showed what they could do with spears—when they attacked them the first they speared was the only good marksman.’

This description is not recorded elsewhere but vitally important in putting together what happened in the lead up to the massacre. It shows the Blacks were drawing out the shepherds to discover who were the best shots.

It would appear the Blacks planned to attack in the days prior to the event for, ‘when they attacked them the first they speared was the only good marksman.’

This account does not appear in any of the records of the time and suggests Mr Faithful withheld information – what other information regarding the attack was withheld?

Lady Franklin wrote in her diary her opinion of William Faithful saying he, ‘seemed a person of no great intelligence—a giant in size.’

Of his sister, Alice Gibson, Lady Franklin wrote she, ‘seemed to gain confidence by his presence and talked more and loudly.’

The remainder of Lady Jane Franklin’s diary entries relates to her impressions of Sydney and descriptions of the dignitaries she stayed with until her return to Hobart.

Her diary is a wealth of information about times we can only imagine and I am grateful she had the presence of mind to leave us such treasure.

THE REFERENCES;

(1) This Errant Lady, the journal of Lady Jane Franklin

(2) Australian Dictionary of Biography – Lady Jane Franklin

(3) Australian Dictionary of Biography – Dr Edmund Charles Hobson

(4) Dr Hobson’s journal excerpts are found in This Errant Lady, the diary of Lady Jane Franklin. The complete journal can be found at The Stae Library of Victoria.

(6) https://portphillippioneersgroup.org.au/pppg5fn.htm

(7) The Moth Hunters by Josephine Flood

(8) http://press-files.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/p198511/pdf/ch052.pdf

(9) Edward Micklethwaite Curr, Recollections of Squatting in Victoria. https://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/721936

(10) profile on Dignum & Comerford, Comerford’s statement.

(11) GA Robinson, Journal 39-52. Sunday 6th June, 1841

This 1816 Portrait is by Amelie Romilly