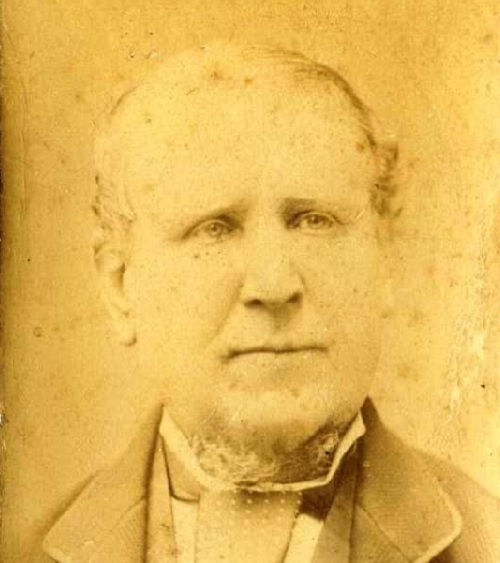

was born in Rathkeale, Limerick, Ireland 24th June 1815 and was transported to Australia as a convict in 1836. (4)

JC Bourke was under the offer of a pardon if he delivered the mail between Melbourne and the Murray River for one year. He had a tight time schedule to adhere to if he wished to be granted his pardon. This put him under much pressure to succeed. (1)

He wrote letters later in life reflecting on his adventures and these give us great insight into the challenges he faced crossing flooded rivers and navigating the wilderness of the Sydney road in 1838. (2)

However, JC Bourke was desperate to gain his pardon but to do so he had to adhere to a gruelling schedule to see the mail arrive on time. He wrote of riding one horse to death.

Bourke wrote of using a stick to beat the horse to keep the animal moving for he was in such a hurry he could not allow time to rest or eat. Just before reaching the Goulburn River, the place of his next supply of horse his mount dropped dead and Bourke had to walk the remaining mile.

This is also a man who had deadly exchanges with indigenous people. He wrote that when the mail load became heavier and he was told to take a pack horse he was quite concerned about the handicap of holding the lead of an extra horse. He wrote that if he needed to defend himself how could he possibly fire a gun while holding the reins of his horse plus an extra one.

JC Bourke wrote that only his employer, Joseph Hawdon knew the details of the scapes he encountered with the Blacks.

Bourke had to be careful about keeping such knowledge secret as the government made it clear indigenous people were subjects of the Queen and no acts of indiscriminate reprisal could be sanctioned. The penalty was death so Bourke needed to keep quiet about his actions. He was already a convict and the courts would look poorly on him.

The Beginning of the Mail Run

The winter of 1837 was said to be one of the severest in the history of the colonisation of Australia. Rain fell on 42 consecutive days. (Charles Bonney The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954)

Joseph Hawdon had crossed the Murray River the year before with Hepburn and Gardiner and now returned with his brother, John Hawdon.

The Hawdon brothers, Joseph and John reached the flooded Murray River in the winter of 1837 and decided to cross the swollen waterway by removing the wheels from a dray and strapping a tarpaulin under the body of the vehicle. The same method Joseph had used the year before. (3)

The result was a rough punt they launched into the stream in the hope of having it drift across by the aid of a tow rope. However, the rope broke and of the three men on the punt only one could swim so John Conway Bourke dived into the flood and succeeded in guiding the punt across the river.

After congratulating JC Bourke on his rescue Joseph Hawdon proposed that someone then should swim the river bearing a rope to help the others across. However, no one was keen to volunteer to enter the raging flow of the river. However, after some discussion, JC Bourke agreed to brave it a second time and a few hours later the whole party was safe on the Victorian side. (6)

Joseph Hawdon was so impressed with Bourke’s willingness to face challenges he made an offer telling the young man he intended to make a proposal to the Governor to carry the mail between Melbourne and Yass and if successful Bourke could have the job.

Hawdon was granted the mail run for £1,200 a year and true to his word sought out Bourke and offered him the job.

Bourke was working at the Punch Bowl, an abattoir on the site now occupied by flats in Toorak Road, near the South Yarra station at the time.

Carrying the mail was a dangerous and challenging task through what was then a wilderness with only wheel tracks showing the way.

On the morning of January 1, 1838, John Conway Bourke, armed and rationed with the mail for Sydney waved farewell to the assembled citizens outside Scott’s Hotel, Collins Street and set out to deliver the mail.

He was accompanied by Michael O’Brien, who was to ride with him as far as the Goulburn where Joseph Hawdon was waiting.

A retinue of 14 squatters, liberally charged with champagne, escorted the pair as far as Mount Alexander Road, Flemington and by nightfall they reached Kilmore.

This marked the end of the known country; thereafter Bourke went ahead compass in hand, while O’Brien blazed the route on the tree trunks.

After they reached the Goulburn, Bourke continued the journey alone, aiming for the Hawdon’s Howlong station on the Murray River.

His horse bogged in the soft clay of the Murray shallows was stuck fast so Bourke stripped and swam the river to seek help from the men at Howlong station where he had been told he would find a hut and yards with someone waiting to greet him. He found a yard only.

Undaunted, he walked naked toward some lagoons, where he saw the hut. But on the way a pack of kangaroo dogs attacked him, and he climbed a tree, from which, he was presently rescued by Mr. Wetherell, the superintendent at Howlong, who at first took Bourke for a bushranger who had been stripped by the Blacks.

On returning to the river an attempt was made to rescue the horse, but the animal was drowned. The journey to Howlong had taken six days.

Halfway through 1838 the amount of mail increased to the point where Bourke had to travel with a led horse. His mailbags weighed 15 pounds. (5)

Bourke was not impressed that he needed a packhorse saying it meant both hands were employed leaving no way to hold a gun and fire if he were attacked.

He wrote in his letters that ‘his name was a terror to the blacks’ and he alluded to killing more than one saying only Mr Hawdon knows the true number.

JC Bourke wrote a series of letters when aged in his 60’s speaking of his adventures. These letters were written in an attempt to persuade the government to give him a pension for his service in undergoing the dangers of the mail run in 1838.

The letters give a rich insight into the era but also give disturbing accounts of brutal treatment to Indigenous people.

Cross-referencing the events with other authors gives a richer tapestry but there is also a feeling Bourke is talking up his role for the purpose of impressing the government of his heroism in the hope of being granted a pension.

His letters must be read with that in mind.

On about the 1st April 1838 he spent a night on the Ovens River camping with WP Faithful’s men. He later wrote this was when he became acquainted with James Crossley and the other shepherds. (2)

Some days later he arrived at Mr Clarke’s on the Goulburn River and heard that James Crossley had arrived with a tale of how his shepherds had been attacked at the Broken River. Clarke had given Crossley a horse and Crossley had ridden to Melbourne to alert authorities. (2)

When JC Bourke arrived at the Broken River he wrote of finding the body of one of the shepherds whom he recognised by the man’s long yellow hair. He said the body was naked, face down, the head pounded in while eagles had eaten the man’s thighs.

He wrote he knew this man having camped with him and the rest of Faithful’s men on a bend of the Ovens River just 10 days before.

When JC Bourke arrived at Col Henry White’s on the Oven’s River the rest of Faithful’s men and animals were there. Bourke said Col White and his son Ned, had been there about a month and intended to set up a station on the banks of the King River near the junction. (2)

After the massacre of Faithful’s shepherds, Col White travelled south and took up a station at Sunday Creek.

Col White had a boat at the Ovens River and took it with him. This disappointed Bourke enormously as he well knew the dangers of flooded rivers so had been looking forward to quick settlement at the crossing places between the Murray and the Goulburn so he would have boats, huts, a yard to keep his horse, cooked food and company on the nights he camped out. (2)

Bourke blamed the Blacks involved in the Faithful massacre for the halt in settlement and his letters show a disregard for the rights of indigenous people suggesting he never forgave them.

He later wrote about many narrow escapes from the Blacks in 1838 taking the mail ‘…It was to Mr Hawdon only that I communicated the actual circumstances that occurred to me during the year.’ (2)

CH Eden wrote a stinging letter to the editor complaining that squatters were at the mercy of the Blacks because if they shot them they could face the hang man’s noose.

Ebden wrote under the name, ‘A Matter of Fact Bushman’, and his letter of February 1839 was titled ‘Further Black Atrocities’. The letter was penned on the banks of the Murray River at Cumberoona Station which was at that time in the hands of Henry and Charles Fowler. (2)

The letter was inspired by JC Bourke’s incredible tale of escape from three hostile indigenous men on the Sydney road near Holbrook who intended to kill him. (2)

JC Bourke’s account of the attack was greatly embellished to portray him as an innocent man suddenly come upon and who turned the tables in his favour by courage and extreme athleticism that outclassed his indigenous foe.

In later years he seemed unrepentant for inciting fear and aggression towards indigenous people. Certainly, Ebden’s letter made a furore among squatters who decided it safest not to speak openly of retaliations they made towards indigenous people.

Bourke wrote that indigenous people were aware of his task carrying the mail and understood it was the white man’s way of communication. (2)

At the end of 1838, JC Bourke finished his role as mailman and worked for Joseph Hawdon as a stockman.

Bourke later became the first licensee of the Westernport Hotel, at the corner of Queen Street and Flinders Lane. But his prosperity slowly ebbed around 1858, and a decade later he was given a subordinate position in the post-office from which he was retired with a modest pension in 1883.

JC Bourke always maintained it was he who suggested camels for the Burke and Wills expedition, thus, ironically, making possible the most tragic page in the history of Australian exploration. (2)

For his role as being the first mailman in Victoria, JC Bourke was granted a pardon.

Some reports list him as travelling with Major Thomas Mitchell on his third surveying expedition in 1836 but this is yet to be researched.

John Conway Bourke died at the age of 87 years at Flemington on August 8, 1902.

Melbourne cemetery

THE REFERENCES;

(1) Historical Records of Victoria Vol 2A, pg 321.

(2) John Conway Bourke, Letters 1886 held at The Royal Historical Society of Victoria, Melbourne.

(3) Capt John Hepburn, Letters From Victorian Pioneers.

(4) Australian Town and Country Journal article printed Wed 25th Feb, 1903 pg 40

(5) Trove, 27th Oct 1928 by Frank Whitcomb. The Weekly Times

(6) The Argus, Sat 5th Jan 1935, pg. The author was Mr. Cronin