John Jobbins was a convict (1) who became a wealthy man with large cattle runs supplying his butchering businesses in Sydney. In 1836 he arrived at the crossing place on the Murray River and took up Cumberoona and Talgarno stations. Jobbins had a ruthless attitude toward his fellow man, in particular, Indigenous people. He ordered the Aboriginal people off the land and hacked to death an elderly man for drinking milk from his house cow. Jobbins’ most notorious act was leading the Dora Dora massacre where 12 Indigenous men, women and children were slaughtered. (2) (3)

John Jobbins was born on 10th November 1793 and at age 20 stole a sheep, value 4 shillings, and gave it to his father, Peter Jobbins born in 1765, to sell in the family butcher shop in Easton-Grey, North Wiltshire, England.

His father, Peter Jobbins was found guilty of selling stolen property and was transported to Australia for 14 years. He arrived in Australia on 9th October 1813 onboard ‘Earl Spencer’, he was 63 years of age. (4)

John Jobbins arrived in Australia just two years later having been convicted of stealing clothing (value 38 shillings). He arrived in Sydney aboard the convict ship ‘Fanny’ on 25th August 1815. (1) He was 22 years old on arrival. The ship he arrived on was the first to bring to the colony the news of the battle of Waterloo and England’s victory over Napoleon. (17)

At the expiry of his sentence, John Jobbins began a butcher shop near the wharf and according to the Colonial Secretary’s papers, he received an assigned convict. (8) His business quickly became a success and in the 1828 Census Jobbins was living at Cambridge St. Sydney with his profession listed as a butcher. Also at the house is Sarah Chamberlain wife and housekeeper and John Jobbins Jnr. child. Business must have been doing well as sharing the Jobbins home was William Henry Simpson 37yrs. Clerk and Joseph Ireland 10 yrs.O/C. Lodger. (5)

But then tragedy struck the Jobbins household as reported in the Sydney Gazette – 11th March 1830 pg 1 column 1

‘At 10 o’clock on Tuesday morning an inquest was held at the sign of the Saracen’s Head, Gloucester-street, Rocks, on the body of a fine boy, about 6 years of age, named John Jobbins, who was unfortunately drowned in a well at the back of his father’s house, No. 31, Cumberland Street, Rocks. The jury, upon the clearest evidence, returned a verdict, that the deceased was-“Accidentally drowned in an exposed, unprotected, dangerous well, at the back of his parents’ residence.”

Such a loss was made greater by the fact that Sarah Jobbins never gave birth again. The couple remained childless until 1836 when they took in Sarah’s niece, whose mother had passed away and in 1839 they adopted 3 orphaned siblings – William, Isabella and Mary Ann Park. (6)

John Jobbins threw himself into his business and by the late 1830s had contracts with the militia to supply meat. (7)

Contracts to supply the militia caused Jobbins to need a steady supply of beasts to fulfil his contracts and manpower to help run his enterprise. Manpower to run his business was provided by the government in the form of assigned convicts. The aims of assignment were to reduce the number of convicts the government had to look after, provide farmers with cheap labour and clear convicts out of the town of Sydney. By 1836, nearly 70 per cent of all the convicts in NSW were working as ‘assigned convicts’. Upon arrival in the colony convicts who had trades were a valuable commodity and highly sought after. Reading through the assigned convict lists is fascinating reading as there were butlers, milk-maids, cooks and shoemakers. It is easy to imagine the eagerness of colonists to peruse the lists of newly arrived convicts searching for those who had skills they could use.

John Jobbins also availed himself to convict labourers and among their trades were butchers, silver platers, a nail maker, stonemason and cooper. (9)

A ‘cooper’ has the craft of making barrels of wood bound with metal hoops and this skill was invaluable in the meat business of the early 1800s. Preserved meat was in high demand by overlanders and ships about to take to sea and barrels were the best way to store it.

Procuring a steady stream of carcasses for his butchering business must have been difficult because according to court records John Jobbins returned to his old ways and butchered stolen animals.

In 1826 John Jobbins was accused of stealing a pig, the property of George Cribbs. At the subsequent trial, George Cribbs gave evidence to prove that the stolen pig, which had been found hanging in Jobbins shop, had indeed been his property. Nevertheless, Jobbins was found not guilty. (6)

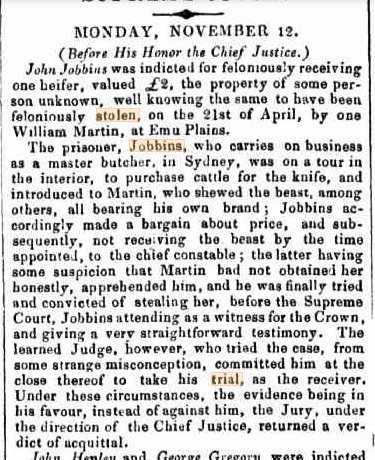

And again on 21st April 1832, Jobbins offered 1 pound for a heifer believed stolen and on 18 Nov 1832, Jobbins claimed he bought the beast from William Martin of Emu Plains. The judge urged the jury to acquit Jobbins.

A fuller account can be found in The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1803 – 1842) Tue 13 Nov 1832 Page 2 Supreme Court.

Jobbins was an important man in Sydney providing meat for colonists and the militia. Was this the reason he was never convicted of stealing?

Jobbins appears to have been a hard master as there were at least two assigned convicts who absconded from his service. One was Francis Nott a Butcher from convict ship Isabella 1832 who ran away 13th Jun 1832 and the other Joseph Moffatt 42 a stonemason, black comp, black and woolly hair, black eyes, eyebrows black, nose broad, a man of colour and a man who would have been reluctant to abscond for his appearance would make him hard to hide.

Then there was poor Joseph Knight, a man who would have run away if he’d known of the punishment to be afflicted upon him. Knight was Jobbins’ shepherd and when this unfortunate man brought the sheep in one evening the flock was said to be one short. Knight was accused of being negligent in his duties and was sentenced to receive 50 lashes. (10)

Jobbins was determined to be a wealthy man so was unwilling to be at the mercy of stockholders demanding high prices for their animals. He wanted land so he could supply his own.

John Jobbins took up land on the Yass River at Gundaroo and called the property ‘Nanima’ in about 1833. However, it was not long until he wanted more land. (6)

John Jobbins took up Cumberoona run, on the north of the river and shortly afterwards took up Talgarno on the Victorian side of the Murray River. (2)

According to AA Andrews, First Settlement of the Upper Murray, pg 43, John Jobbins overheard a private conversation by two chaps intending to take up Cumberoona run. Determined to take Cumberoona up for himself, Jobbins immediately set out on a forced march to beat them to the Commissioner’s office. Apparently, he made no friends in the act for there are no reports of John Jobbins by his peers showing him in a good light.

The information of Jobbins brutality and murder of Indigenous people comes from white accounts. This was unheard of in early days as white settlers closed ranks refusing to name their neighbours in acts of aggression against Indigenous peoples. Yet JFH Mitchell’s telling of Jobbins actions shows us Jobbins was not well thought of by black or white. (11)

According to JFH Mitchell, John Jobbins while at Cumberoona discovered an elderly aboriginal man drinking milk from his house cow. Outraged by the theft, Jobbins took his cutlass and in a fury hacked the old man to death.

How long Jobbins held Cumberoona is a mystery as AA Andrews wrote Jobbins sold to Charles and Henry Fowler in 1841. However, JC Bourke the mailman in 1838, wrote that he visited the homestead at Cumberoona in Jan 1839 and it was already in possession of Henry and Charlie Fowler. (12)

The historical search for John Jobbins shows he was plagued with troubles with his fellow man. Jobbins ran an advertisement in the Sydney Herald, Friday, Oct 1st 1841,

ALL persons having purchased Cattle from me are hereby cautioned not to remove any Cattle in or about the Murray, without first making it known to me, or my storekeeper George Pratt, my having lost a hundred head from my Station, bearing my brand. Any person withholding the cattle bearing my brand after this date will be prosecuted accordingly.

JOHN JOBBINS, September 18, Nanima.

And on more than one occasion John Jobbins was set upon by bushrangers along the Sydney road. On one journey he attempted to outwit the thieves by, ‘hiding his money in a girl child’s clothing.’ (13)

This surprising act gives an insight into John Jobbins moral code for he considered bushrangers would not interfere with a child. Yet, Jobbins recognised the child as a hiding place for valuables showing his mind was of far more devious nature than the bushrangers.

There is the case of Hoskins vs Jobbins where Jobbins endeavoured to eject the plaintiff from a parcel of land under the Small Tenements Act, however, the plaintiff was left in possession. Jobbins was not content with this result and brought a quantity of diseased sheep onto the land which had the desired effect of driving the plaintiff away. Jobbins then took possession of the land. (14)

Then there was Jobbins vs Darlott where the promise of a sale of cattle was reneged upon when the stockman turned up to collect the animals from Jobbins and he refused to hand them over. (15) Conflict with his feloow man seemed to plague Jobbins.

There is the suggestion of price collusion in the butchering business when, ‘The Australian,’ Thursday 11th November 1841, pg 3, mentioned John Jobbins as getting an excellent price for his beasts while other cattlemen received a pittance. The article claimed, ‘Sydney butchers are offering ‘one penny’ for stock in a wish to glut the market and sell to the hungry at five pence.’

According to Dorothy Mulholland in Far Away Days, Jobbins ‘hunger for land was enormous and he quickly gained the nickname ‘Rich John Jobbins’. (6)

JFH Mitchell wrote that Jobbins ordered Indigenous people from Cumberoona, a favourite camping place and became such a monster to them that they fled at the sight of him. The Indigenous people wrote a ‘hate hymn’ according to JFH Mitchell to sing about their loathing of him.

F. H. Mitchell said a good many of the words had no equivalent meaning in English, being “blackfellow curses”. One line went something like this: “Nein-mudder, Bel-mudder, Jobbin, Jobbin merijole”. Mitchell said, ‘the meaning of the first two words was quite unprintable, and the balance signified that Jobbins was a wicked rascal.’ (11)

There is no doubt John Jobbins behaved in a violent and cruel manner to the Indigenous people upon whose land he profited yet he had the audacity to complain when they fought back.

The Sydney Herald of 26th Oct 1839, pg 2 printed a letter from John Jobbins complaining of troubles with Indigenous people. It is titled, ‘from my station, named Tawonga, on the Kiewa River.’

Sir, I beg to submit to you a copy of part of a letter received from my stockman, dated 2nd October 1839.

Sir, I write to let you know that we have been attacked by the Blacks, they threw a shower of spears at us which, happily, took no effect; one spear passed under the arm, close to the shoulder, of the hut keeper. We certainly must have been murdered had it not been for the providential appearance of old ‘ Tom,’ Mr Robert’s man — they went from the hut and commenced spearing the cattle, of which they killed a considerable number, and drove the rest all over the bush, so that it is impossible to tell what mischief they have done yet — we are trying to collect them as well as we can — I beg you will come up, and send some person to take charge, for I am very uneasy in my mind about those Blacks, not knowing one hour from another that they may come and murder us all, and plunder the place — we heard them on the other side of the river next morning — one said, that could speak a little English, that they would come again before long. If you do not come, or send some persons, we shall be obliged to leave the place, and your cattle to go where they like our lives are in danger, and you cannot expect us to stop and be murdered.’

I give you the letter just as I received it, and if the Government does not interfere in some shape or other, people’s property will be sacrificed, together with the poor men’s lives. I have been striving, for a number of years for what few Cattle I have, and to be plundered in this manner by the Blacks is very unpleasant, — more so as I have always acted with the greatest kindness towards them, and I am confident my men have done the same. There is not a time when teams go there but I supply them with rations and blankets, which I send purposely to be distributed amongst them. By giving this a place in your widely circulated paper you will much oblige,

Your obedient servant,

JOHN JOBBINS. Namina, near Yass October 10, 1839.

John Jobbins’ assertion, ‘I have been striving, for a number of years for what few Cattle I have,’ is such an outright lie that it must be put forward for what it is. In 1839, when the letter was written Jobbins was a wealthy man. He had a large brick home at Nanima, Gundaroo plus Cumberoona, Talgarno and Tawonga. (6)

AA Andrews gives an indication of how much land John Jobbins held around the Murray River alone. Talgarno was 40,000 acres estimated to carry 2,000 cattle. Tawonga 20,000 acres estimated to carry 440 cattle. Cumberoona 21,812 acres estimated to hold well over 1,000 head of cattle. The logistics to manage these runs would show that Jobbins was running a massive operation.

At the same time Jobbins had land in inner-city Sydney that he was leasing for 50 pounds per year and was receiving income from his military contracts and butcher shops so could hardly be considered a poor man.

But the assertion, ‘I have always acted with the greatest kindness towards them,’ (referring to Indigenous people) is another outrageous lie. John Jobbins ordered Indigenous people not to set foot on Cumberoona, hacked an elderly Indigenous man to death with a cutlass and led a massacre of twelve indigenous men, women and children. (11) (3) (18)

But who wrote this letter to the editor of The Sydney Herald as according to Lea-Scarlett, Errol, 1972, Gundaroo, Roebuck, pg 30, John Jobbins and his wife were illiterate.

According to Dorothy Mulholland, ‘Letters exist which show Jobbins signature, although that could only be established by a handwriting expert.’ (6)

John Jobbins must have been pleased when a letter appeared in the papers painting him in a good light. The letter pleads that John Jobbins was a benevolent man, kind, courteous and generous, yet plagued by attacks by ungrateful Black savages.

The Sydney Monitor & Commercial Advertiser on pg2, Monday 18th November 1839.

The anonymous author wrote Mr Jobbins was known for his, ‘sheer hospitality to people of all grades and colours, is a great sufferer by the aggression of the blacks; and what makes it more vexatious is that he tries by all human efforts to conciliate them, furnishing them with blankets and provisions every time his teams go up, and going to the expense of having brass plates engraved with appropriate devices, to be distributed among the chiefs.’

Signed, Your CORRESPONDENT. Gundaroo, Argyle, Nov. 11, 1839.

This letter does not equate in any way with the John Jobbins we have read about. Historical searches show evidence John Jobbins was a thief, a cruel master and a murderer.

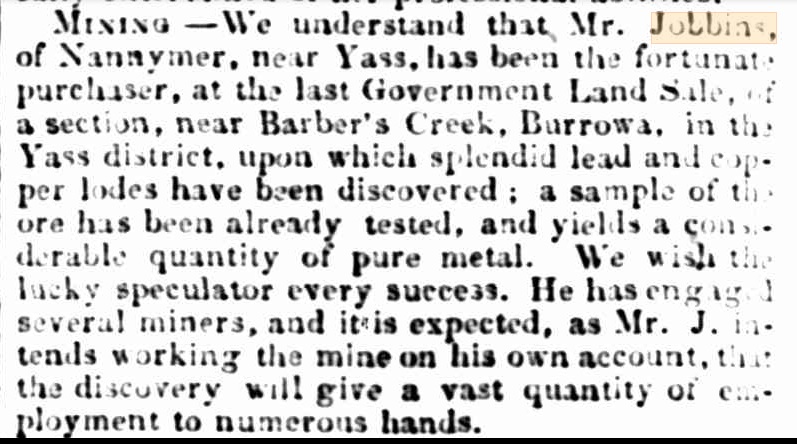

Yet Jobbins was to have a stroke of good luck in a land purchase as printed in the Bells Life in Sydney & Sporting Review, 29th May 1847

So John Jobbins added miner to his list of incomes and when he died at Nanima on 8th January 1855 he left property worth over 80 thousand pounds which in today’s money would be more than 4.3 million dollars.

At the time of his death, Jobbins was building a row of terraced houses in Sydney which are still in existence. Jobbins Terrace at 103-111 Gloucester Street is listed as historically significant. (16)

He was described as, “an enigmatic figure, shadowy, somewhat mysterious, a man of many parts with conflicting values”. (6)

THE REFERENCES;

(1) https://convictrecords.com.au/convicts/jobbins/john/91338

(2) AA Andrews, First Settlement of the Upper Murray

(3) https://c21ch.newcastle.edu.au/colonialmassacres/detail.php?r=574

(4) https://convictrecords.com.au/convicts/jobbins/peter/112681

(5) 1828 Census NSW

(6) Dorothy Mulholland, Far Away Days – A history of Murrumbateman, Jeir and Nanima districts.

(7) Thomas Walker’s, A Month in the Bush.

(9) https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/230389812?searchTerm=assigned%2C%20convict%2C%20convicts%2C%20John%20Jobbins# 27th Feb 1833, NSW Government Gazette, #52

(10) YDHS Archives, Bench Books, 16 November 1836.

(11) J. F. H Mitchell (John Francis Huon), 1831-1923. Aboriginal Dictionary and papers held at State Library Melbourne.

(12) Letters by John Conway Bourke, held at The Royal Historical Society, Melbourne.

(14) 15th Feb 1851, The Goulburn Herald. https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/101731687?searchTerm=Jobbins%2C%20diseased%20sheep%20Hoskins%20vs%20Jobbins%2C%20diseased%20sheep#

(15) 5th Dec 1843, https://trove.nla.gov.au/newspaper/article/37125015?searchTerm=Jobbins%2C%20Darlott%20cattle%2C%20stockmen#

(17) https://dictionaryofsydney.org/artefact/fanny#ref-uuid=3d9dabe5-2805-a1ea-2186-4b09f3397593

(18) Colonial Frontier Massacres Dora Dora

Record of Jobbins, https://www.paperturn-view.com/?pid=NDM43341&p=349&v=1.1