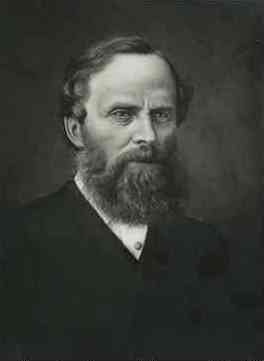

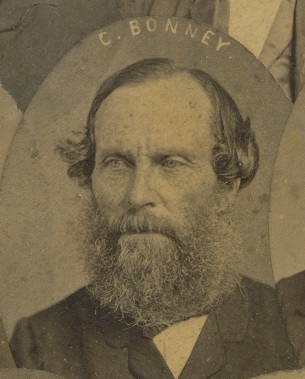

Charles Bonney was born on 31 October 1813 in England and in August 1834 at the age of 21 sailed for the colony to take up a position as a clerk for Judge William Burton. (1) (3)

After a voyage of 18 weeks, he landed on 12 December 1834 in Sydney and began work, staying in Burtons employ for about nineteen months. (3)

Bonney resigned his position midway through 1836 to help his friend Charles Hotson Ebden set up Ebden’s new stations on the Murray River. Just how he met Ebden is still to be discovered. (2) (3)

Bonney left Sydney in July to help Ebden manage his stations, Mungabareena and Bonegilla.(3)

A short time later Bonney was sent to search for an overland cattle route to Melbourne but it being a wet spring, the Ovens River was in flood and he was unable to find a way across. (3)

He returned to Ebden’s sheep run where shearing was in progress. (3)

A second attempt to find a route to Melbourne was commenced on 25 December 1836 with a bullock dray and seven men. (3)

Some accounts place Ebden with Bonney on this second journey, which was completed on 7 January 1837 when the party arrived in Melbourne, just days behind John Gardiner, Joseph Hawdon and John Hepburn, the first to bring cattle overland from New South Wales. (1) (3)

Melbourne at that time consisted of a few huts with one newly-erected freshly painted weatherboard store. Bonney returned to Sydney by ship and headed overland to meet up with Ebden again. (3)

On 1st March 1837 Ebden and Bonney drove 10,000 sheep from Mungabareena station on the Murray and reached Sugarloaf Creek, a tributary of the Goulburn River on about 14 March 1837. (3)

During the journey, one of Ebden’s shepherds, George Comerford asked Bonney for arms as he’d heard tales of how dangerous the blacks could be towards travellers. (3) (6)

At that time it was commonplace to tell stories of the savage nature of the blacks to frighten travellers heading south along the Sydney road. (6)

Because of this Comerford had a great fear of the blacks and begged Charles Bonney to be allowed a brace of pistols to defend himself if it became necessary. Bonney obliged and later wrote that the pistols were returned without issue. (3)

The voluntary return of the firearms was a surprise as shortly after this event George Comerford turned to bushranging and murder. (See the profile on Dignum & Comerford) (3) (6)

When they reached Sugarloaf Creek, near Kilmore, CH Ebden gave Bonney 1,000 sheep and some men and left him there to set up a station. Ebden then continued on with 9000 sheep to set up Carlsruhe station, arriving there on 26 May 1837.

After the long journey, Charles Bonney was in need of supplies but before he set out for Melbourne he received news from George Hamilton that two bushrangers were hovering about.

Bonney wrote, ‘In company with one of Mr Hamilton’s overseers I spent an afternoon in searching the country roundabout in the endeavour to find the bushrangers, but, not succeeding, I had to start the next morning with the drays for the settlement. On this journey, I made the track which afterwards became known as the Sydney Road, and I also discovered at the same time the fertile district, named afterwards, Kilmore, where I formed a sheep station.’ (3)

Upon his return, Bonney discovered that the two bushrangers, accompanied by one of Mr Hamilton’s men had visited his camp and induced six of his men to abscond with them. (3)

The bushrangers were not heard from again until some weeks later when they returned. However, this time Dignum and Commerford were alone. (3)

Bonney wrote, they, ‘visited the camp during my absence and taken away with them as much provisions etc as they could carry; amongst other things a favourite little gun which had been made especially for my father when, from the growing infirmities of age, he was unable to carry his double-barrelled fowling-piece.’ (3)

Whilst the bushrangers were robbing the camp, the hut keepers asked them what had become of the other seven men who went away with them, to which they replied in an evasive manner, “that they did not know”‘. (3)

After the robbery, Dignum and Comerford proceeded along the overland track towards the Murray River taking with them another of Bonney’s assigned servants, Frederick Hallem.

Bonney wrote, ‘On arriving at the Murray, Commerford gave himself up to the police then stationed there, and confessed that he and Dignum had murdered their seven companions and burnt their bodies.’ (3)

Frederick Hallem is said to have left company with the two bushrangers and handed himself over to William Wyse at Ebden’s Bonegilla station on the Murray River. (7)

After this latest raid by Dignum and Comerford and the loss of yet another man, Bonney was desperately short of workers.

He became despondent of his situation and sent one of the flocks back to Edben at Carlshrue, the rest he moved on to Kilmore where he remained with them till the end of 1837. (3)

Bonney later wrote, ‘Being the farthest outstation from, the Port Phillip Settlement, and there being no other station within a distance of nearly twenty miles, I found the difficulty of managing the sheep so great in consequence of the trouble I had in getting men that I gave up the station and took the sheep to Mount Macedon.’

Joseph Hawdon was at that time preparing to overland stock to Adelaide and Bonney said, ‘I eagerly embraced the opportunity of gratifying my love of exploring new country and joined his party.’ (3)

Bonney met up with Joseph Hawdon at the Goulburn River on 17 January 1838 and they travelled down the Goulburn to the Murray. (3)

On the journey, they tried to follow Major Mitchell’s descriptions but found the Goulburn River took a far more northerly route than Mitchell had stated. They eventually found the Murray river but discovered other inaccuracies in Mitchell’s directions and decided to follow the Murray river rather than place reliance on Mitchell’s descriptions of the country. (3)

Charles Bonney had a gentle nature and was a peacemaker as shown by his dealings with indigenous people during his travels with Hawdon.

He wrote, ‘It was somewhere about the junction of the Murrumbidgee that we first established friendly relations with the natives. Up to this time they had generally avoided us, but from this point the tribes used to assemble to see us pass, and send forward messengers to tell the next tribe of our approach. Once only were we in danger of coming into collision with them. It was my work to load the drays (while Mr Hawdon looked after the stockmen) and sometimes ride ahead to see what country there was before us. On this occasion, I had directed the bullock drivers to go round the edge of a lagoon whilst I rode on to examine the country ahead.’ (3)

‘It seems that a tribe of natives, who were near the drays when I left them, went along the bank of the river to see the drays pass at the other end of the lagoon. The men mistook this for a hostile manoeuvre, and on my return, I found the two parties drawn up in battle array, the men with their guns ready to fire and the natives with their spears poised for action. The men hastily explained the situation in answer to my inquiry as to what was the matter but, from, my knowledge of the customs of the natives, I knew the men were mistaken as to the intended attack and I told them to put their guns down and then rode up to the natives and made a well-known sign to them to lower their spears. They immediately obeyed the sign and we passed on in peace. Many collisions with the natives have no doubt occurred through similar misunderstandings.’ (3) (5)

Bonney’s calm reaction to a situation that could have resulted in violence was a far different outcome than Major Mitchell’s when he met with indigenous people at a similar place along the Murray just eighteen months earlier.

Major Mitchell had no idea how to negotiate with indigenous people and when he felt threatened by a similar situation he ordered his men to shoot.

In May 1836 Mitchell and his surveying party had been followed for several days by a group of Aboriginal people on the banks of the Murray River. Rather than attempt negotiation, Mitchell and his men launched a surprise attack on 27 May which became known as the Mount Dispersion massacre where at least seven indigenous people were murdered.

Mitchell later published a book in which he justified the ambush as an act of self-defence. (8)

An enquiry was held to look into the affair and Major Mitchell received a minor reprimand for the killings.

However, when we look at Bonney’s reaction to a threatening situation we see his cool thinking defused what could have been another massacre.

Joseph Hawden kept a journal and wrote in it of Bonney’s peaceful approach with the indigenous people they met. The following accounts are found in Joseph Hawdon’s book, ‘Journal of a Journey from New South Wales to Adelaide performed in 1838.’

Charles Bonney travelled with a small flute which he would play around the fire each evening. Hawdon wrote that one day there appeared hostile aboriginals on the other side of the river and Bonney played his flute and soon all were friends.

Another time, when Hawdon was threatened by an indigenous man who pushed him with his tall digging stick, Hawdon reached for his gun. Thankfully, Bonney was present and told jokes to put everyone in good humour.

The influence of Bonney’s first employer, Judge (Sir) William Burton should be considered in this.

Judge Burton was Bonney’s first employer when he arrived in the colony in 1834. (9)

Burton was also the presiding judge at the second trial of the men accused of killing 28 unarmed Aboriginal people in the Myall Creek massacre on 10 June 1838. (10)

A group of landowners funded a formidable defence team to represent the accused on trial. They became known as the ‘Black Association’ and allegedly set out on a program of intimidation and advised jurors to absent themselves from court.

The defendants’ counsel advised his clients to remain silent or deny knowledge of the murders during the trial. Despite the damning evidence presented, the jury declared all 11 defendants not guilty after less than 20 minutes’ deliberation.

A second trial took place presided over by Judge William Burton which saw many of the men called for jury service fail to appear.

When the trial finally took place the jury took just one hour to deliberate. The foreman announced that the verdict was not guilty, however, one of the jurors immediately informed the court that the foreman had delivered the wrong verdict and the correct verdict was guilty. An enquiry took place again presided over by Judge William Burton and finally, the guilty verdict was upheld.

The guilty verdict was not a popular one but Judge Burton said the crime was committed in the sight of God, and the blood of the victims cried for vengeance.

All seven prisoners received the death penalty and on 18 December 1838, the condemned men were executed by hanging at the Sydney jail in George Street.

Judge Burton went against public opinion when he pushed for a guilty verdict and it should be noted that this was the first time white men were condemned for killing blacks.

Perhaps Burton and Bonney’s abhorrence of violence is what brought them together. Burton and Bonney’s names are linked as holding the Kilmore run in 1837, as mentioned by George Comerford in his statement. (7)

Joseph Hawdon also referred to the Kilmore run of Bonney and Burton noting in his journal on 4th January 1838, ‘We halted at the rich and well-watered stock station of Messrs. Bonney and Burton, thirty-six miles northward of Melbourne.’ (5)

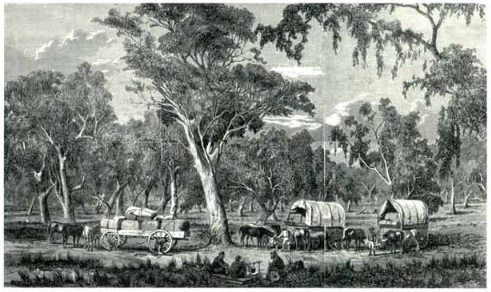

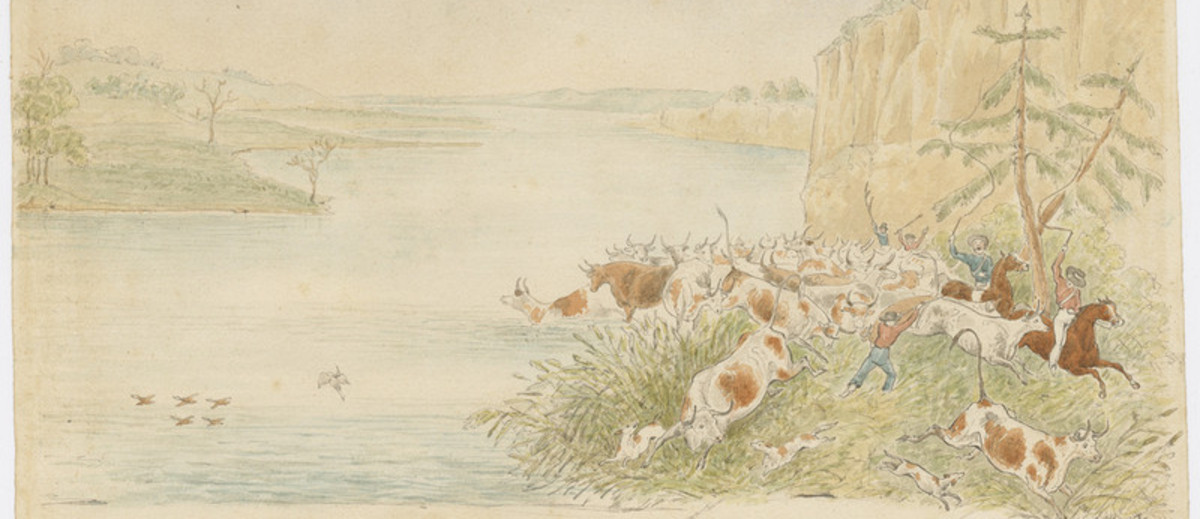

The indigenous inhabitants of the Murray were curious about the visitors and their great mob of cattle, drays and oxen, a cavalcade of the likes, they had not seen before.

Bonney wrote, ‘The natives often assembled in considerable numbers but were perfectly peaceable and caused no annoyance. Messengers being sent on from tribe to tribe to give notice of our approach.’

Near lake Bonney, which Hawdon named after his travelling companion, they ‘fell in with two natives who gave them to understand by signs that they belonged to a tribe some distance down the river and wanted to travel with them. This they were allowed to do, and they made themselves very useful as guides.

Finding a solid surface along the river banks was hazardous as some areas were covered in thick sand which would bog a dray causing a delay in the journey. However, once the natives joined them such difficulties were overcome.

Bonney wrote, ‘I was amazed at the intelligence they displayed before they had been half a day with us they knew as well as we did where a dray could go and where it could not go; although they had never soon white men before they never once made a mistake as to when we could keep the flats and when we must take the high land.’

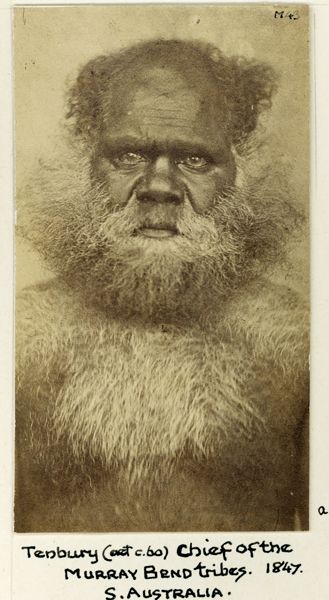

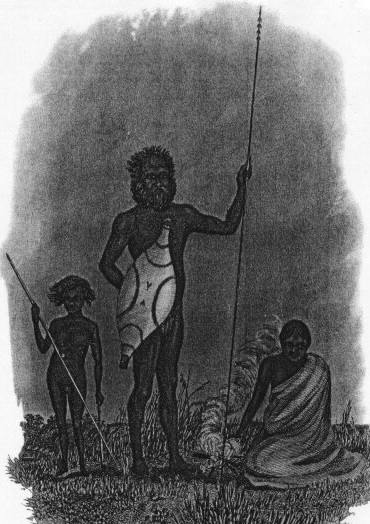

These natives were well known in Adelaide afterwards, and a drawing of one of these men known as Tinberry is given in ‘Eyre’ s Australia’.

Drawing of Tenbury (Tenberry) with wife and child by George Hamilton

Hawdon and Bonney were treated like heroes when they arrived in Adelaide with their cattle. The people of that newly established settlement had been living on kangaroo meat and anything else they could find.

Early in May Bonney left in the Water Witch for Melbourne and since there was no chart and he was the only one on board to ever enter Port Phillip bay he acted as pilot. (3)

On arriving in Melbourne, Bonney was subpoenaed to Sydney to be a witness at Comerford’s murder trial. (7)

The N.S.M. revenue cutter ‘’Prince George” was about to take ‘prisoners and witnesses’ for the Supreme Court sittings at Sydney. Bonney joined the other witnesses on board the ship and they set out for Sydney in May 1838.

Upon reaching Sydney Charles Bonney waited several weeks for a summons that never came. Bonney stayed at Camden during this time and wrote it was during a great drought and although it was winter, ‘the ground was as brown and bare as the middle of the road.’ (3)

Bonney then travelled to Howlong, Hawdon’s station on the Murray River and in early February 1839, Bonney was ready for a second journey to South Australia. (11)

He started from Hughes Creek near the Goulburn River about 26 February with 300 cattle, two bullock drays and ten white men and two indigenous boys.

They travelled through south-west Victoria rather than following the River Murray, a longer but safer route. Near the border, the country became very dry. The horses were almost too weak to carry a rider and the men were in desperate need of a drink. Bonney ordered a calf to be killed so the men could drink its blood.

Fortunately, water was found soon after, and when the Murray was crossed only one bullock and one horse were lost. In spite of their difficulties, only 23 cattle were lost on the whole journey.

Bonney spent some years in South Australia but returned to Port Phillip about April 1841 to take up a station, again at the Murray in partnership with his old friend Ebden. (Kerang or Bonegilla?) (3)

When this venture failed early in 1842 due to a period of depression leading to cattle becoming almost unsaleable Bonney gladly accepted an offer from Governor (Sir) George Grey to become commissioner of crown lands in South Australia. He left Port Phillip in the Iona, took office in May and his appointment was confirmed in November. His main task was to define the boundaries of pastoral leases which until then had been described haphazardly. In this office, he was so successful that in 1854 some crown tenants in the south-east of the colony presented him with £700 as a mark of esteem. (1)

In 1880 Charles Bonney retired on a pension and in 1885 he went to live in Sydney. He died there on 15 March 1897. He left a widow, two sons and three daughters. (1)

Bonney belonged to the best type of pioneer. He quickly adapted himself to the conditions of his new country, was an excellent explorer, and understood how to keep the aborigines in good humour. In later years he was a successful public official, held in great respect by the people of Adelaide. (1)

THE REFERENCES;

(1) Australian Dictionary of Biography – Charles Bonney

(2) Australian Dictionary of Biography – CH Ebden

(3) Auto Biographical notes written by Charles Bonney on TROVE https://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-360332043 Autobiographical notes

(4) The Chronicle (Adelaide, SA) Saturday, 20th March 1897. Obituary. THE LATE Mr CHARLES BONNEY.